Modern GPUs are ferociously powerful compute engines. The RTX 4090 (NVIDIA’s latest consumer GPU) can perform a theoretical 1.3 teraflop/s of FP64 compute, which is about the same as ASCI Red, a $70M, 1600 sq ft, 104 cabinet supercomputer that was active until 2006 [1][2]. This comparison is actually heavily biased towards ASCI Red (below) because the 4090 is optimized for lower precision arithmetic. It blows my mind that this supercomputer from just ~20 yrs ago is FLOP for FLOP, about as performant as a box that fits in one hand!

ASCI Red Supercomputer, ranked first on TOP500 in 2000 [1]

The performance characteristics of GPUs are a bit misunderstood, as they are fundamentally throughput machines, and not latency optimized. One common statement I have read online surrounds how much faster GPUs are than CPUs. A table comparing memory and arithmetic latency for a modern CPU and GPU are below.

| Component | CPU Time (ns) [3][4] | GPU Time (ns) [5] |

|---|---|---|

| FMA | 1 | 5.2 |

| Register Access | 0.3 | 5.2 |

| L1 Access | 1 | 25 |

| L2 Access | 2.5 | 260 |

| DRAM Access | 63 | 520 |

By most metrics, CPUs are significantly lower latency (faster) than GPUs. Another metric we could compare with is thread to thread communication latency. Just to make a point, lets compare communication overhead between threads on separate CPU cores/separate GPU streaming multiprocessor.

A CPU can accomplish this in just 59ns [7], while this parameter is undefined for the other camp because there is no mechanism for direct communication between SMs in GPUs! What good are GPUs for then? While GPUs may have high latency and lack robust inter-block communication, they have vastly greater chip die-area dedicated to arithmetic as compared to scheduling/caching on CPUs. This allows GPUs to excel in workloads that involve little serial(연속적인) communication but lots of arithmetic. A great analogy is that of GPUs being a school bus, and CPUs being a sports car. When a school bus is full and moves from point A to point B, it achieves great person-miles/hour metrics. A sports car on the other hand, can move from point A to point B much faster than the school bus but cannot compete in person-miles/hour. While we don’t traditionally think of school busses as particularly ‘fast’, if utilized correctly, they can certainly provide person-miles/hour metrics that not even the fastest race cars can come close to.

In 2012, a team from the University of Toronto smashed records in a global academic computer vision challenge known as ImageNet [8]. Prior to this result, most of the CV community had tackled this challenge using hand-engineered feature detectors and traditional machine learning algorithms. Alex K, Ilya S. and Geoff H. showed however, that an artificial neural network fed with sufficient data and compute could learn features that performed far better than hand-engineered approaches could achieve. One could argue, that the breakthrough in the AlexNet paper was not algorithmic or terribly novel in its nature (Yann LeCun had shown conv nets programmed with back-prop worked in 1989 [9]) but was largely enabled by Alex K’s expertise in GPU programming*. This breakthrough is what lit the explosion of recent DL progress and while the ingredients for the AlexNet breakthrough had been around for a while, what had been missing was the computational power to train a large enough neural net to digest the entire ImageNet dataset, coupled with GPGPU (general purpose GPU) code to make the neural net go brrr.

*this isn't totally fair, AlexNet was much deeper, wider, used ReLus for the first time, and introduced some new regularization tricks. I don't think the authors would disagree with my assessment though. On a fun note, Alex Krizhevsky's original CUDA code from 2011 is still archived on Google Code! Having a copy stored locally honestly feels like keeping a piece of history!

Deep Learning has characteristics that are very ideal for filling up our big GPU school bus with lots of data and learned parameters! Specifically, the conv net that the UofT team trained involved large amounts of highly parallel arithmetic (matrix multiplies). In the decade since then, artificial nets have digested ever larger datasets on even larger GPU clusters and smashed records in practically every problem with an input-output relationship not easily defined deterministically. While there have been waves of various neural net architectures since 2012 (CNNs, RNNs, Transformers, SSMs, etc) the core DL ingredient of lots of matrix multiplies has not changed much. Over the next many posts on this website I’ll be sharing my learnings on deep learning inference optimization enabled by an understanding of GPU architecture. While these posts focus on NVIDIA GPUs and use CUDA, the general concepts of parallel-programming apply to any GPU based architecture.

Its worth noting that GPUs are certainly not the only way to accelerate deep learning workloads, and will be competing against other approaches over the next several years. Notable contenders include TPUs (Google), Dojo/AP car computer (Tesla), WSE (Cerebras), Grayskull (Tenstorrent), IPUs (Graphcore), and something with analog memresistors (Rain). While I have thoroughly enjoyed learning about GPUs over the past month, I am actually quite bearish on GPUs (and really anything based on the Von Neumann architecture) for DL inference projecting into the far future. I am in the camp that believes biological neural nets, at a high level of abstraction, aren’t all that different from artificial nets. Lets run with this thinking: imagine if every time a biological neuron fired and the action potential reached the synpase, our brains had to go run somewhere (thousands of neurons away) to figure out what ‘weight’ is associated with this connection. Our brains would be horribly inefficient! But this is basically what modern GPUs are doing, utilizing lots of energy on this memory movement, and spending relatively little on the compute itself. Analog approaches with weights implemented in hardware will take time to figure out and scale but will better suit the task of doing lots of dot-products when compared to their digital equivalents. A fun thought experiment is that of a DL accelerator built from very tiny mechanical springs. The law which governs spring behavior (Hooke’s Law, $F = k x$) has the same form as the input to an artificial neuron ($y = w x$). One could imagine hooking up compressive/tensile springs with different stiffnesses (weights) to plates (neurons) and implementing a ReLU non-linearity by preventing these plates from displacing in the negative direction. If you scaled this out you’d have an incredibly energy efficient mechanism for neural net inference! All you’d have to do is modulate the input plates and measure the position of the output plates, with the only energy losses being minimal heat generation from internal spring stresses. I am not saying this is practical, but it goes to show how elegant and universal the idea of the neuron is. It’s quite unlikely that GPUs are the final stop in the quest for a computational substrate capable of artificial general intelligence.

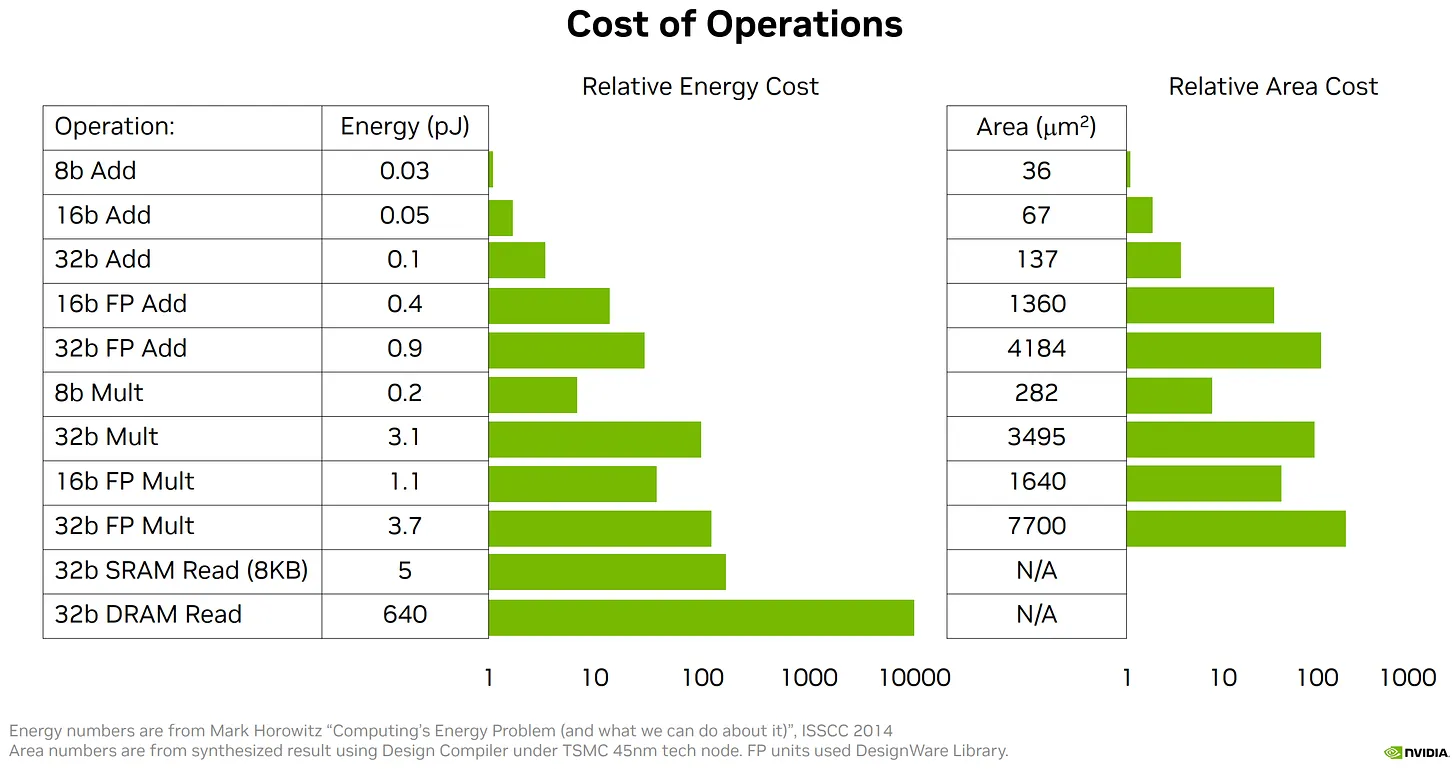

Energy consumption for a 32b DRAM read is ~200x that for a 32b multiply! [10]